Last weekend I was in Manchester. Like most of us, armed with a camera, I was excited to do some street photography. Whilst I’m not a street photography expert, I love the idea of a concrete jungle that has been layered up over hundreds of years, from old granite and brick buildings to new, skinny, modern, imposing buildings that reach for the sky.

And I also love the people within these places of wonder. The idea that you can have all different cultures, ethnicities, or races. People who have lived there for generations to tourists wandering aimlessly through the busy streets makes it a fascinating thing to shoot, and for a photographer, it means you constantly need to change, adapt, or you’ll leave disappointed.

Black and white photography has always been alien to me. I didn’t grow up in a time where it was the norm, nor have I ever really gravitated to it before. Fujifilm is so well known for their custom sims. We know this, and I’ve always kept a black and white sim ready for when I ever thought the time was right. And last weekend in Manchester, I felt the time was right.

Now I’ve kind of tabled in black and white photography, using spot metering. I know spot metering isn’t black and white photography, but I often use it with harsh light to create strong contrast in my images. This leads to them giving off a middle ground of the two. You don’t get big, vibrant images, but you don’t also lose all the colour in the image.

Armed with this skill, I made a decision when I was in Manchester to look differently to shoot in black and white. Why? Well, because the colours of the city weren’t speaking to me. Sounds hippy, I know, but I didn’t feel, given the grey, cloudy, rainy sky, that the colours of the city were popping. Manchester without the right light in my option can be a very muted city (depending on where you go). Given this, though, I didn’t want to miss out on any opportunity or leave Manchester wishing I’d taken more photos. That’s why I switched to black and white.

I felt like black and white photography was the right choice for this weekend in Manchester for a couple of reasons, and I hope by laying out my reasons it might inspire some of you to not just try shooting in black and white but to try experimenting more when you feel something is off and not to just give up and put the camera down.

Firstly, black and white photography, by its very nature of the fact you have no colour, removes unwanted distractions and helps you focus on other aspects of the photos you are taking, such as light, people, shapes, and the chaos of life. All of these, of course, are amplified greatly in a city, and the results are even greater because of this,

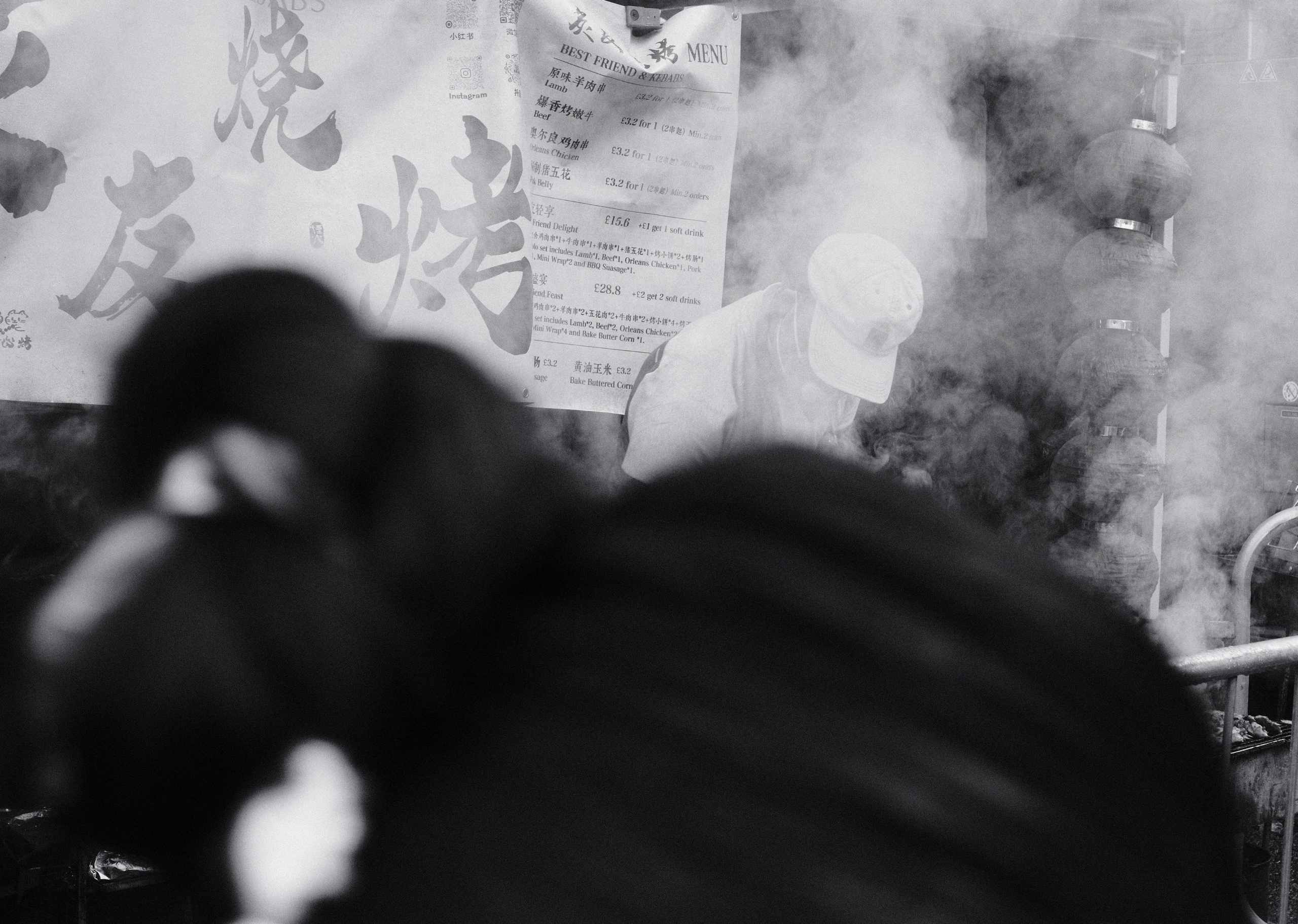

Look at this example, taken in Chinatown in Manchester. Now, I shoot JPEG plus Raw, so I know that the raw file version of this image looks very different.

By stripping the photo, however, of all its colour, in my opinion, brings it to life and, like I’ve just spoken about, focuses us to look at different aspects of the image, such as the people in this image. We have two very different people from totally different perspectives, which I think asks a lot of questions, and something an image should do is ask questions and try not to give the answer away too easily.

This image also, because it is in black and white, helps to bring out the chaos. Clearly, we are in a market of some sort. Clearly, the photo is at a food stand, and by the nature of one of the subjects, clearly cooking, and well, we don’t exactly know what he is cooking without looking closely. Ask “what is he cooking?” “Is he busy?” He looks with incomplete focus, so we probably assume he is very busy.

And as for our other subject in the image, we have so many questions adding to the chaos, like “who is she?” “Does she work there?” “Is she queuing in line for this food?” Or she simply someone who wandered in front of my camera lens.

What black and white also forced me to do that weekend was start thinking in terms of contrast. Not colour contrast, but tonal contrast. The difference between light and dark. The way shadows sit against highlights. The way a person in a dark coat can stand out against a pale wall without a single bright colour in the frame. When you remove colour, you don’t lose depth. You just have to find it somewhere else.

Take the portrait I shot inside the café. The light was soft, coming in from the window, nothing dramatic. In colour it would have been pleasant, nice skin tones, warm interior. But in black and white it became about the light on her face, the catchlights in her eyes, the subtle shadows around her cheekbones. It simplified everything. You’re not thinking about what colour her jumper is. You’re looking at expression, light and tone.

That was something I kept noticing across the weekend. Shadows, patterns, textures and lines suddenly became far more important.

In the kitchen shot through the doorway, it’s not the stainless steel or the white walls that make the image. It’s the repetition of the hanging lights, the clock on the wall, the shape of the worker leaning over the counter. The frame within a frame. The darker pillar on the right balancing the lighter workspace on the left. All tonal decisions.

Then there’s texture.

The two mugs stacked on the tray. Simple scene. In colour it would be white mugs on a grey background. Nothing special. In black and white though, you notice the shine of the ceramic, the subtle shadow under the lip of the mug, the smoothness of the tray against the harder metal kettle behind it. You start to see surfaces rather than colours.

The same with architecture.

That glass building with the lone figure stood on the corner balcony. The whole frame is lines and symmetry. The criss-crossing structure behind the glass, the strong verticals and horizontals. In colour, it would have just been another grey building under a grey sky. In black and white, it becomes graphic. Almost abstract. It feels colder. More isolated. Which matched the weather perfectly.

And that’s something else I realised. Grey days are made for black and white. Manchester gave me rain, flat skies, and muted streets. Normally, that might frustrate you. You want golden hour. You want colour. But winter has its own mood. Umbrellas lining up outside in the rain. Reflections on wet pavement. People hunched in coats. It already feels colourless.

When I photographed the group under the umbrellas, the scene wasn’t about bright tones. It was about repetition. The shape of the umbrellas. The way they almost merge into one mass. The contrast between the dark coats and the lighter fabric above. The rain streaking through the frame.

Colour would have distracted from that. The same goes for street photography in general. Street photography is about the human condition. It’s about moments. Expression. Body language. Tension. Curiosity.

That man stood against the brick wall with the crowd moving behind him. In colour, you might focus on what people are wearing. In black and white, you focus on him. His posture. His expression. The way he feels separated from the flow of people behind him.

And the mirror shot in the market. A small rectangular mirror hanging off a stall, reflecting a child’s face back towards me. The surrounding scene is busy. Plastic sheeting. Poles. Movement. But the reflection cuts through all of it. In black and white, it feels quieter. More direct. It becomes about that gaze.

That’s when I realised something important. You don’t just “convert” an image to black and white. You have to shoot for it. You have to start looking for strong blacks. Clean highlights. Leading lines, and shape. Shape. You have to notice how a shadow falls across a pavement. How steam rises against a darker background. How a phone box covered in stickers becomes about texture and wear rather than red paint.

You start asking different questions.

Where is the light coming from?

What is the darkest part of this frame?

Where is the brightest?

Is there enough separation between them?

And the more I shot, the more natural it felt. Black and white stopped feeling alien.

It started feeling intentional. I didn’t worry too much about heavy editing either. I was already using a Fujifilm black and white simulation, so I could see the tones live through the viewfinder. I adjusted exposure slightly, sometimes leaned into the shadows, sometimes lifted them. Occasionally added a bit of grain for texture. But I kept it simple.

Because the goal wasn’t to over-process. It was to see differently.

Manchester didn’t give me vibrant skies or glowing sunsets. It gave me rain, steam, glass, concrete, and people moving through it all. And instead of fighting that, I leaned into it.

Switching to black and white wasn’t about giving up on colour. It was about adapting. About not putting the camera down just because something felt off. And that’s probably the biggest takeaway from the weekend.

If the colours aren’t speaking to you, change the language. Experiment. Try something different. Force yourself to see light instead of hue. Shape instead of shade. Contrast instead of vibrancy. You might come home with a set of images that feel completely different to what you normally shoot. And sometimes that’s exactly what you need.

Blog

Gran Canaria with the X100VI: Photo Diary

Why Places Like Belton House Are Actually Great for Photography

Can the Fujifilm X100VI Handle the Great Outdoors?